Started on March 7 of 2006 by Amit Gupta and Luke Crawford in New York City, Jelly was one of the earliest modern manifestations of pop-up-style coworking that really achieved a strong following.

It originally was run once every other week out of just one location, a five-bedroom loft apartment at 56 W. 39th Street known as House 2.0. House 2.0 was a small coliving community that had its own web site and frequently hosted events and parties.

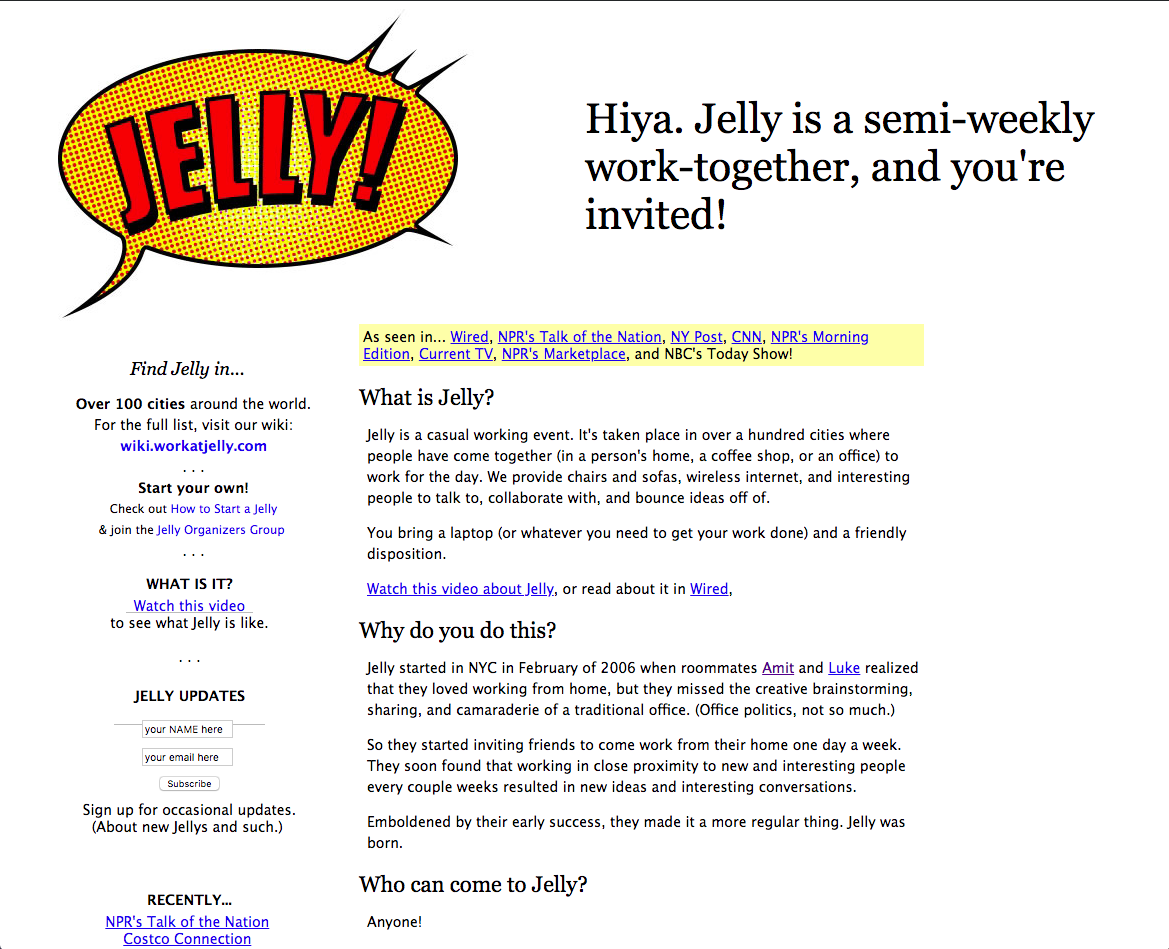

The core idea behind Jelly was simple: Amit and Luke work from home. Some of their friends work from home, too. Every now and then, let’s get together and work in the same place. We’ll get work done, have fun, and maybe make some new friends!

From the original blog post:

Here’s the deal: Luke and Amit both love working from home, but they find that spending the occasional day working with others really helps get the creative juices flowing. Even though everyone’s working on their own projects, they can bounce ideas and problems off of each other and have fun doing it.

What’s Jelly? Jelly’s our attempt to formalize this weekly work-together. We invite you to come work at our home. You bring your laptop and some work, and we’ll provide wifi, a chair, and hopefully some smart people.

While you’re here, you can discuss and work with others, or move somewhere where you can work solo without distraction. It’s up to you. The goal is to give you a good, productive workday.

I confess that, until I wrote this post, I called March 14, 2006 the birthday of Jelly—that was the date Amit’s blog post was published. I’ve since posted several times on this day to celebrate the annual anniversaries of Jellies.

His post, however, clearly states that the first Jelly gathering was on the previous Tuesday.

A radical idea: inviting strangers into your home to hang out and work

I was shocked that I could simply add my name to the wiki and show up. I emailed Amit to be sure I really could do this, and he responded assuring me that this was the point and I was welcome.

Acts like this at this point in time paved the way for a greater sense of comfort with the idea of interacting with strangers, both in coworking spaces but also in around-the-corner soon-to-launch mega-platforms like Airbnb and Uber.

I’ve since come to understand that being open to the public doesn’t mean there’s no curation whatsoever: implied barriers can help shape an audience.

In this case, only people who heard about it could attend—plenty of people walking by House 2.0 on the street had no idea what was going on upstairs. You had to know where to look to find it, which drastically cut down on the potential pool of attendees.

Secondly, you had to have a use for it—namely, you had to have the ability to work from someone else’s couch. That meant, most likely, work based on a laptop with wireless connectivity, which at the time was a very small portion of the population.

Being open while still maintaining some implied limitations is a nuanced and valuable thing.

Minimal programming with maximum impact

There was no formal program to Jelly, though there were some handy constructs that helped facilitate connection.

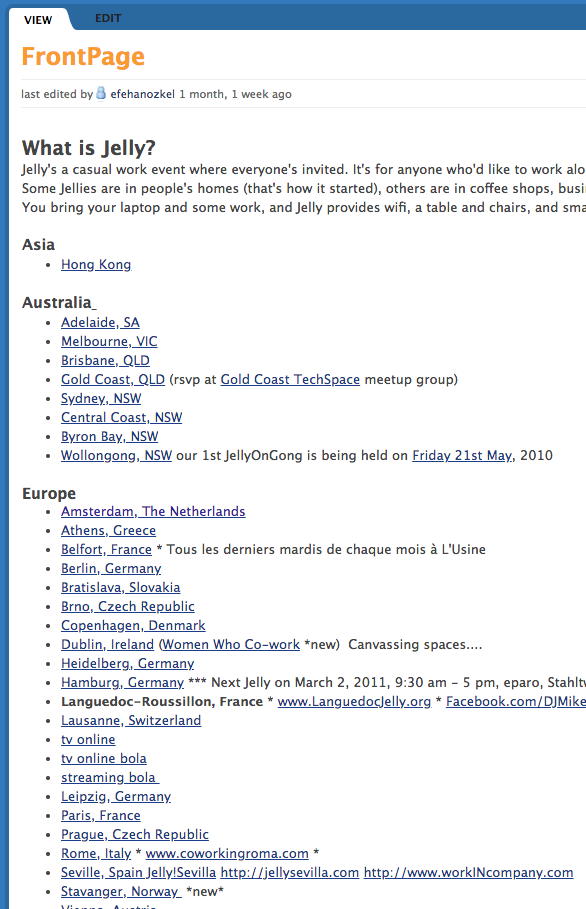

A Jelly would have a start and end time, and people could show up anytime during that time. To secure a spot, you had to add your name and what you’d be working on to a wiki page for the day you were planning to attend. Each Jelly event had its own wiki page which was used to coordinate details.

This also served as a handy record of who attended which session, which has proved invaluable to me when I’m trying to recall who I met and how to get in touch with them.

You can even see the wiki page for the first Jelly I ever attended, on March 15, 2007, here!

This served as a tremendously effective way of preemptively connecting the participants, as each attendee could see who else was coming and what they were working on before they arrived.

This is one of the ideas from the early days that never quite carried over into the mainstream coworking world that I think should one day be resurrected in future programs.

Attendees would grab a spot wherever they liked in the apartment and get to work.

Crafty facilitation

After some time I realized that Amit practiced a crafty facilitation technique: he simply asked random friends what they were working on, knowing full well that their response would elicit the interest of others within earshot.

When two people got to talking about something that arose from the conversation he started, Amit would sometimes disappear, his job as a connector completed.

Jellies would be very casual—they were in a home with big cozy couches and secondhand furniture after all—with anywhere from a handful of people up to 20 or more in attendance. It always felt very cozy and intimate.

The level of talent of the people in attendance always floored me. From the first day I ever participated in a Jelly I felt like I was in the company of remarkable people, and indeed, many of the people who participated in Jelly in the early days went on to achieve significant notoriety for their professional accomplishments.

Once anyone could organize one, Jelly spread quickly.

Spreading from NYC to 100 cities around the world

On September 1, 2007, Amit moved to San Francisco, leaving the organizing of Jelly in NYC to a small group of dedicated friends, including Darrell Silver and myself.

On that same day, I moved into House 2.0, and was already well underway working to build upon what Amit and others had started.

Jelly continued to happen either weekly or once every other week, at House 2.0 and at other locations around the city. We experimented with working in people’s company offices and other homes in Manhattan and Brooklyn.

As I was at this point also preoccupied with CooperBricolage, the cafe-based coworking community I was dedicating myself to, I split my time between working on that and continuing to stay active with Jelly.

As he transitioned to San Francisco, Amit started working to reconfigure Jelly to become something anyone could do anywhere—simply by copying the idea and creating a separate set of wiki pages on the Jelly site.

He led the charge by starting his own chapter of Jelly in San Francisco, drawing the participation of some now famous tech startup entrepreneurs who were at the time in their earliest stages.

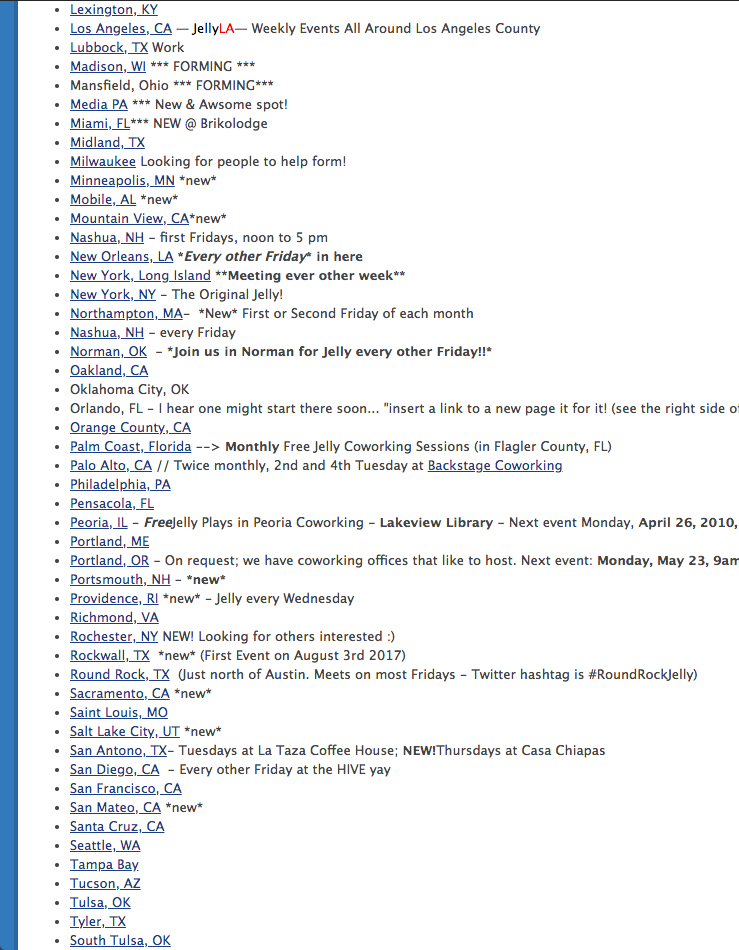

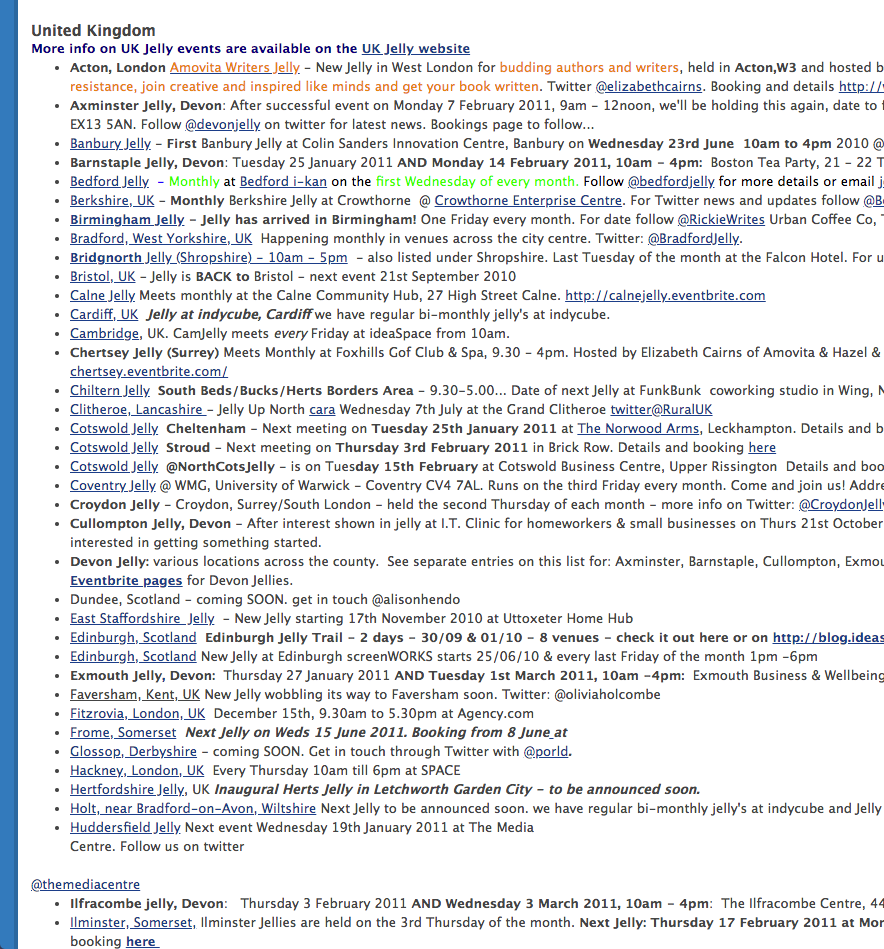

Meanwhile, around the world, more people started to create Jelly events of their own.

Paving the way for coworking spaces

Jelly quickly became known as a great way to seed interest in a potential established coworking space, because it was free and easy to start and because it attracted the kinds of people who might likely be interested in joining a coworking space.

One of coworking’s earliest champions, Chris Messina, dubbed Jelly “the gateway drug to coworking.”

Jelly waxed and waned over the proceeding eleven years. As of this writing in 2018, there are still Jelly groups happening around the world, though they’re hard to keep track of at this point.

Until I sat down to write this, I had assumed that Jelly had all but petered out, with only a handful still happening.

Upon further research, however, I discovered that new Jellies are indeed being formed even at the time this was first being written (in late 2018).

Jelly has been a major hit in the UK, with its own dedicated web site. A new Jelly will kick off in January of 2019 in Bicester UK, which has its own web, Facebook, and Twitter pages.

Jelly’s impact on the global coworking movement is without question, with at least dozens of coworking spaces if not more owing their origins to Jelly.

How did the word Jelly come about?

I believe that the origin of the name “Jelly” has been deliberately kept a mystery—I’ve personally head conflicting explanations as to its origins from Amit himself.

One time he claimed that it sounded similar to a word that carries a more specific meaning in an Indian language. Another time, he said that when he and Luke were originally discussing the idea there was a bowl of jelly beans on the table and that provided the inspiration. I’ve heard at least one or two more explanations over the years as well—you can try to ask Amit, but I kind of prefer letting it be a bit of a legend of its own.

Further Reading

- Jelly home page

- How to start a Jelly (wiki page)

Cover photo source: Amit Gupta